Pierre Le Franc

A novel that recounts, through the work of men and women, the evolution of the science that led to the development of cardiac stimulation. A fascinating text in a lively, spirited style.

Back cover

At the end of the 15th century, old Anthonius died surrounded by his family, leaving his son the vision of paradise he had seen a few days earlier. This anecdote is the prologue to a great epic that will take us from the Enlightenment to today's world.

Pierre Le Franc recounts the evolution of science by following the work and lives of men and women who practiced a new way of thinking.

This great human and scientific adventure progresses at the pace of ideas, inventions, discoveries, joys, passions and dramas, culminating in the development of electrical stimulation of the heart.

As the story unfolds, the author plunges us into a reflection on the movements of thought and knowledge, to help us better understand the origins of the world in which we live.

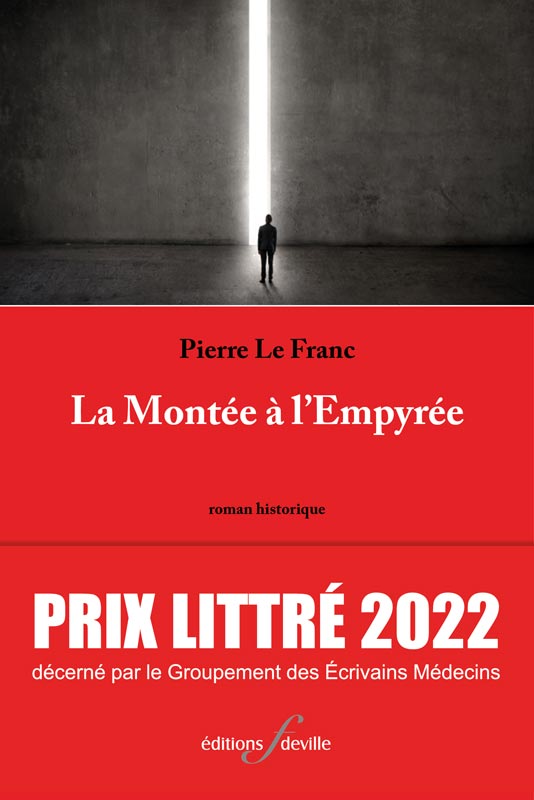

In the upper part of the painting, against a background of darkness, a luminous tunnel was outlined with bluish walls. At the end of the tunnel radiated a bright glow of absolute purity. Below, in the midst of the clouds, guided by angels, souls in prayer ascended toward the light

Physician and cardiologist Pierre LE FRANC has been practicing cardiac stimulation for 30 years. After practicing cardiology in various regions of France, Reunion and Canada, he has been based in Rouen for over twenty years.

Since 2015, he has published a number of short stories.

Ascent into the Empyrean is a historical novel spanning several centuries. It features real events and characters fictionalized for historical purposes. Starting with the Enlightenment revolution, it tells the story of the evolution of science that led to the development of cardiac stimulation.

This book can be read like a novel, with real or fictional characters who sometimes cross paths several decades apart. It can be read as a human adventure leading from the Age of Enlightenment to the contemporary world. It can also be read as a reflection on the evolution of thought and science over the last three centuries, through the example of pacemaker technology.

We meet genius researchers, but also illustrious politicians whose motives are not always innocent; we travel the world over the course of time; we enter into the intimacy of inventors and practitioners in masterfully painted tableaux; we take part in the fight against death and approach its mystery. Real-life characters blend masterfully with their fictional counterparts. It starts and ends with a Bosch painting. A marvel of literary construction!

The Prix Littré is an annual literary prize awarded since 1963 by the Groupement des écrivains médecins in tribute to Émile Littré, himself a doctor, lexicographer and writer. It is awarded to "works of all genres, in the French language, whose ethics, characters and ideas derive in whole or in part from the humanism that is the very essence of medical ethics".

Interview with Pierre Le Franc

Why this title?

In Greek mythology, the empyrean is the 7th heaven, the world where the gods live, in other words, the ideal world. In the Christian tradition of the Middle Ages, by assimilation, the empyrean is heavenly paradise. The place where pure souls ascend after death. The empyrean is therefore an ideal world that everyone, in their own way, seeks to reach.

It's in this sense that I use the word. My book is built like a staircase. Each chapter, each episode is a step on the way to the final result that everyone sees at the end of the tunnel: an ideal world where technology serves humanity.

Why did you want to tell the story of these scientific discoveries?

Of course, it wasn't my intention to tell the story of cardiac stimulation.

It all started with an observation. Let's take three examples: life expectancy, travel time from Rome to Paris, and the time it takes to get a message from Rome to Paris.

In late antiquity, life expectancy could only be estimated. The first censuses carried out in Rome, the most famous being that of the year zero, give us an idea of life expectancy, which was around 35 years. The transport time for a seasoned horseman from Rome to Paris was one month, and the time to communicate a message was the same, since the only means of communication was the letter carried by the same horseman.

More than 1,000 years later, at the end of the Middle Ages, life expectancy was still 35 years. A horseman's transit time from Rome to Paris was still one month, and his message won't be any faster.

A precise estimate of life expectancy began to emerge in the mid-18th century, with the introduction of the civil registry, which was essentially maintained by the parishes. At that time, life expectancy in France was... 35 years. The transit time for a messenger carrying a letter between Rome and Paris was always the same.

250 years later, life expectancy in France exceeds 80 years, it takes less than 2 hours to fly from Rome to Paris, and communication via the Internet or telephone is instantaneous.

What could have happened over the last 250 years for the world to go from the technological Middle Ages to today's hypertechnological society, when nothing had changed for thousands of years?

This is the question that started me thinking. The answer is obvious: The Enlightenment Revolution enabled men and women to think in complete freedom. We learned to reflect, i.e. to observe and arrive at a conclusion by following a deductive logic freed from the shackles imposed by religious beliefs. It was then that men dared to think, as Kant put it. It was then that new thinkers, not yet known as researchers, began to develop a new way of searching, inventing deductive thinking and experimental science. It's thanks to their work that knowledge is advancing faster and faster. The first title I chose for my novel was Lights and Men. For various reasons, the title was changed, but it still illustrates the first part of my thinking.

What follows is a quest. Ascent into the Empyrean is a search for a world where technology serves humanity. This is the world that the men and women in my novel want to reach. If I chose the theme of the progressive invention of the pacemaker over the course of two centuries, it's because this field lends itself perfectly to the writing of a novel, with its dramas, its joys, its hopes and its disappointments. Its lives lost. Its lives saved. And finally, the goal that has finally been reached today.

To illustrate this revolution, we could talk about transportation, starting with Cugnot's steam engine in the 18th century, then moving on to the development of railroads and the internal combustion engine, and arriving at the electric car or space travel. We could talk about communications, from the air semaphore invented in the 18th century, to Samuel Morse and his famous code, to today's smartphones. We'd find the same progression, the same filiation, the same approach and, ultimately, the same ascent to the same technological empyrean.

In your book, you bring together real and fictional characters. Isn't reality enough?

Reality is what historians do every day. I'm not a historian. I'm a novelist. I think. I dream. I imagine. I create. My mind never stops imagining scenes based on real elements. Imaginary sequels to real events. Possible origins to events that happened.

One day, when I was a young intern, a young woman who had survived cardiac arrest arrived in my hospital beds. She told me about a near-death experience, a disembodied afterlife experience. She saw a light in the sky. She saw her brother-in-law, himself a firefighter, struggling with her body and preventing her from flying away. She tried to talk to him to ask him to let her go, but he kept at it and then, at one point, there were a lot of people around her body and she was sucked into him. She woke up in hospital. As I listened to her, I had in my hands the report of the firemen who came to rescue her. The story she was telling me coincided point for point with the story on the report. It was a very impressive experience.

A few weeks later, I found myself in Venice, where I discovered the painting by Hieronymus Bosch. The similarity between the image presented by the painter and the image described by the patient was so obvious that I couldn't help wondering how a painter could have had this experience in 1485 and still be alive 25 years later.

You're talking about reality. But where is reality? What is reality? No, there was no obvious answer. No reality. So I had to imagine the answer to the question myself. That's how the novelist takes precedence over the historian. I wrote the story much later. It became a short story and then the prologue to my novel.

In "Ascent into the Empyrean", you mention a number of scientists. Which ones do you admire the most, and why?

I've lived with all these scientists for so long. I've done so much research on them. I couldn't tell you which one I admire most.

Aldini, of course, who synthesized the electrical work of Volta with the physiological work of his uncle Galvani. It was he who launched the idea that the electrification of bodies could one day sustain life. He was an extraordinary visionary who developed the landmark experiments I cite at the start of the novel, which enabled others to follow in his footsteps.

There's Lidwill, the forgotten Australian doctor who was the first to save a human life with cardiac stimulation in 1927.

There's the Swedish doctor and engineer who built the first pacemaker in his basement in one night, with very limited resources. The anecdote I quote about using a metal shoe polish can as a mold for the first pacemaker is true. It took a great deal of imagination and nerve to make a device that was intended to save a man's life, and did save it.